It’s interfering with my new work too: I’ve decided it best to push the launch of MONSEY BLUES until I can onboard a professional PR brain to my team (friends: know anybody with Crisis Comms experience?). This is definitely a first for me, but since October 7th I want to have a more skillful hand than mine guiding it into the cultural conversation, because I do not want my story about “Anti-Semitism in America” co-opted into conversations about Israel. That is NOT what it’s about.

Personally, I’m truly trying to STAY OPEN and face all this anger and confusion and pain and hatred that’s gushing out of every mouth, every screen. Tibetan Buddhists practice tonglen ( “sending and taking”): a practice of inhaling suffering — their own and others — and exhaling compassion, for self, others, the world. I’m sitting and practicing this several times a day, trying to keep my heart/mind clear from ANY narratives, focusing only on what serves life.

Let all dead leaves fall away.

So uh, how about a nice story… to pass our time together? One with ZERO judgment or humiliation… unless you’re a 10 year-old artist with a crush.

She was a giant, towering over us kids at six-foot-three.

Cardigan-wrapped and lanky with a pale heart-shaped face and blue-grey cat eyes framed by blue-grey cat-eye frames. Impossibly angular at the elbows and knees, earth-tone socks peeking through her open-toed sandals. She made us wait a full five minutes while she wrote her proper name on the chalkboard — “Ms. Beaumont” — in ornate extra-whorly cursive, then slow-blinked and insisted we never call her that because “Ms. Beaumont” was her unmarried auntie. She chuckled musically at her own joke, like an exotic bird. We were only ever to call her by her first name: “Gail”.

She was our new art teacher. I loved her immediately.

I was new to the Dade County public school system that year, entering fourth grade after two impossibly-wonderful years in a tiny montessori school my parents could no longer afford. Public school was harder-edged in this high-performing district with classes of 200-plus whose teachers constantly fought the school board for basic supplies. My teachers were also clearly struggling — one was mid-divorce, another mid-pregnancy, a third with an explosive temper — and day after day, they checked the boxes on lesson plans and dismissed all critical thinking. No individual attention, no encouragement or love, just earning their weekly paycheck.

But Gail — loopy-sweet Gail! — had a heart I could see when she spoke, beating softly through her second-hand cardigan as she showed us how to blend oil pastels or told us which parts of our parents’ Sunday papers to steal for the best collage materials: real hands-dirty art tips for know-nothing fourth-graders.

All I wanted was to soak in her undivided attention.

That’s because my life at home was tense: my parents were struggling to feed and house us — we were hand to mouth, every month — and despite their best intentions, they took it out on each other all the time. My stay-at-home mom who devoted her life to her boys needed reasurance she wasn’t getting that things were going to be okay, and even though I was only ten, I stepped into those boots with no instruction manual for that kind of responsibility. When fists banged on dinner tables, I cleared the dishes. When road trips got explosive, I secretly reached for her hand and held it.

But who was there for me to turn to, to tell me things were going to be okay? No one, until I found a way to turn inward, into stories. And drawing. I was always pretty good at it — never great — but cartooning just came naturally from a young age. My dear Nana nicknamed me “Danny Doodle”… which I can’t believe I just admitted publicly and fully deserve if that sticks.

And so: as a short, quiet “four-eyed new kid”, I was mostly-ignored when I wasn’t picked on. So I drew. And drew. And drew. All day, every day: through Civics, through Science, through Florida History (Howard Zinn would’ve rolled over in his grave). Sometimes I got caught, sometimes teachers ignored me back, but I started getting attention from the other kids. Four-Eyed New Kid became Kid Who Can Draw Good, and I started taking requests to draw for my bullies: this G.I. Joe, this Star Wars character, etc. I drew so the other kids would like me (and never really stopped).

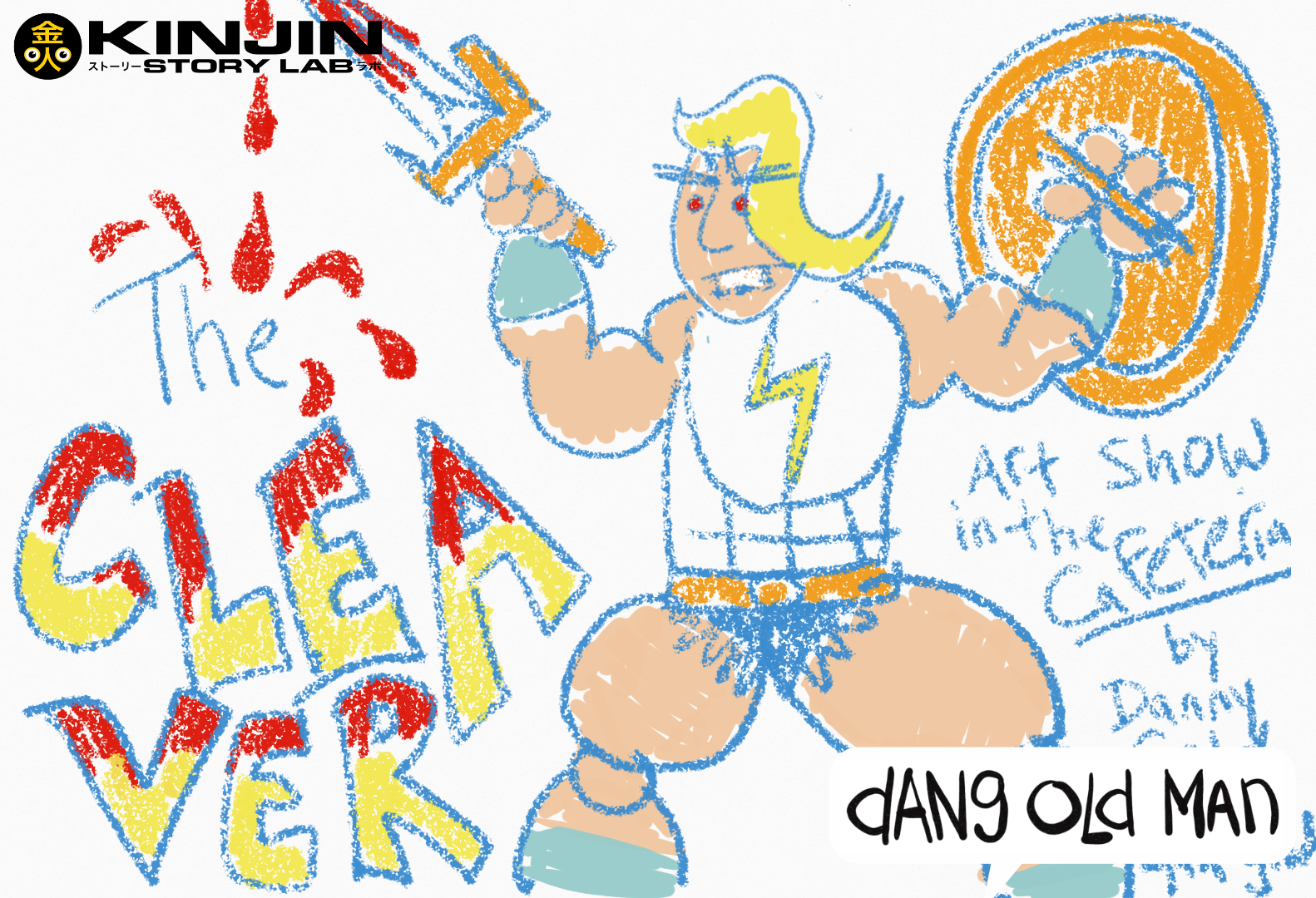

But really, I was drawing for myself, because I had a secret manila folder, and it contained THE ADVENTURES OF THE CLEAVER.

The Cleaver was really a He-Man knock-off, except he rode a pegasus named Lygos instead of that green tiger. I was really into those toys, and spent any free time inventing stories wayyyyyyy more complex and world-buildy (as we say in the biz) than the afterschool cartoon series ever was. So I made up my own version where he fought all the obstacles in his way in single-page comics done in colored pencil and Crayola markers.

The Cleaver was just strong and blonde and overmuscled, but he wielded the Diamond Sword and he was not afraid to use it. When The Cleaver faced an enemy, he’d try to reason with them, realize it was futile, and chop some fucking heads off. There was never happy ending, only a temporary relief until the next creature arrived on the next single-page adventure.

As things at home got more intense — in a bad moment, my mother asked me who I’d rather live with, her or my father — I even withdrew in Gail’s art class. Completely zoning out, I needed The Cleaver to chop heads for me, to remove confusing obstacles between me and a world that contained any love, order or justice. And as I’m sitting there scribbling red jets of blood squirting all over The Cleaver as he lifts the chopped-off head from a monster’s monstrous shoulders, I suddenly smell—

Sweet breath, exhaled.

I know I’m busted, but this time I’ve been busted by Gail. My gut churns because I don’t want her to think I don’t care about her class — beacuse it was everything to me — as her cat-like face looks down on me from her high-altitude world where nothing hurts.

Then she kneels, her body folding like a mantis into a polygon of knees and elbows as she places her hand softly on my shoulder. She stares hard into my drawing:

GAIL: Danny, what are you drawing? We’re all drawing our, um, dream vacations this week. [with compassion] Is this your dream vacation? It looks really… angry.

ME [dying]: I know, Gail… This isn’t my vacation, this is an adventure of The Cleaver—

She stops. Not mad. Her pupils dilate as: artist recognizes artist. God I love her even more now because she sees me.

GAIL: Do you… not want to draw the vacation? Or the other assignments? Be honest with me.

I shrug, half-smile. She’s revealed me and I shake my head. Gail chuckles and it has its own melody. She tousles my hair, tells me to gather my things. Then she leads me across the Art Pod to these desks in the corner we never use. They have partitions for privacy, probably designed for test-taking. She tells me to pick the one I like the most. I pick the one furthest away from the rest of the class, way in the corner, and sit.

Gail takes a kid-sized chair and folds her body into it, her knees almost above her shoulders. Her eyes are twinkling at me as she talks:

GAIL: Tell me, how long have you been drawing… The Reaver?

ME: It’s, um, The Cleaver. A few months. Hm, no. Actually, five months.

GAIL: Are you making up the stories of his adventures too? [I couldn’t speak but my cheeks flushed hot.] Do you remember when you first drew him?

I did. My parents had a fight after I was put to bed and it woke me and my brother up. I could hear my mother crying, my dad slamming the front door and driving off into the night. He was back by the time I woke up the next morning, but I’d already given birth to The Cleaver. I didn’t say any of this to Gail though.

GAIL: Do you have more of these adventures? [I nodded.] Would it be okay if I saw them?

Gingerly, I took my secret manila folder out of my backpack. I’d never shown this stuff to anyone else, not even my brother. But Gail held out her long pale hands and I placed the folder in them. She took her time, flipping through every single drawing. There were probably about thirty of them, rudimentary comic stories scribbled onto crinkled notebook paper.

Her eyes were tearing up and I was afraid I’d upset her, but when she finished, she just smiled big, flashing her crooked-beautiful smile at me:

GAIL: I see what you’re doing with these, Danny. I know how hard it feels, being surrounded by unhappy people, how it can affect people like us. People who pay attention and feel things a little deeper than most.

I could feel tears starting to well up in my eyes that I didn’t want her to see. Boys weren’t supposed to cry, especially not in front of pretty ladies. I closed my eyes and willed the tears back down to wherever they live (I’m so good at it now, been doing that for years).

GAIL: Can I tell you what I see? I see a bright future where your stories can reach — how many of these adventures did you draw? [She counts my pages.] Here’s what I think: if you could draw four more of these and bring The Cleaver to a place where he can find some happiness, I think you’d have created something complete that could help a lot of other kids.

ME: What? Help other kids… how?

GAIL [cat eyes flashing behind cat-eye frames]: How about we start with: [her hands make a your-name-in-lights gesture] a solo art show in the school cafeteria? Where anybody in school could be inspired by The Cleaver’s strength to keep going?

Of course, no one had ever believed in me like that. Ever. Of course I said yes.

++++

There was no deadline, but I spent my next art class isolated in my cubicle. I could feel Gail’s eyes on me as she instructed the normies. The gauntlet was thrown, and I, as author of The Adventures of The Cleaver, needed to find my ending.

But I was stumped. What could it be? I knew it needed an amazing final obstacle for The Cleaver to overcome, like a terrible undefeatable villain, but… The Cleaver already fought monsters on every single page. Another monster is not an ending.

Most days after school, my mom would pick us up in her diesel station wagon and take us to my father’s work, where we’d hang out together until my dad finished work. He had a small space with a few offices: I remember a younger guy named Marty and a blonde woman whose name I could make up here but it’s not worth the effort. Marty was the reason I’m bringing this up.

Because as I sat at the spare desk where the receptionist that got let go used to sit, Marty walked into the office. He was wobbling — at first I thought he was trying to make me laugh — and then my dad got up suddenly and went over to him and hugged him. I remember Marty having dinner at our house a few times but today he looked different: confused, nervous, wiry and older. His gait was off too: not so much a limp as that his legs weren’t working in sync anymore. From his tensed-up forehead, you could see the effort it was taking to control them.

On the ride home, when I asked what happened to Marty, my mother explained that he had muscular sclerosis, but it had suddenly gotten much worse. When I asked if Marty was going to die, my father said:

DAD: I’m going to die, your mom’s going to die. You’re going to die too.

++++

My germ for the ending of The Adventures of The Cleaver had arrived: The Cleaver would reveal that he’d always had a sickness, one for which there was no cure. His own life didn’t matter, but what did matter was his true mission: to find someone to be the next Cleaver to pass along the Diamond Sword and his pegasus Lygos.

I was in fifth gear from there. I cartooned for a week straight, laying down the best pages my ten year-old fingers had ever drawn. I drew through all my classes. I redrew them after school in front of the TV. I refined them all weekend, even while working at the Sunday flea market where my dad and I sold blank VHS tapes.

It was all just coming out of me… and then I — and The Cleaver — found his replacement inside a mystical cave of purple crystals: an ancient mechanical body that was missing its head. And The Cleaver realized: if he could transfer his own head onto this armored body that would never get sick and never die, he could be an even stronger version of The Cleaver, forever.

The Cleaver then asked his loyal steed Lygos for one final favor: to use his pegasus strength to kick off his head and place it atop the metal body, where of course it would attach itself and remain alive because of ancient magic.

And once it was done, The Cleaver was no longer sick. With this stronger version of himself, The Cleaver became his own replacement.

When Gail asked me about my ending, I told her I was almost finished drawing it (some things never change) but I couldn’t hold back my enthusiasm: in the corner of the art room, with wild gestures and flashing eyes, I laid out the whole ending… and she applauded. She thought it was perfect and… “poignant.”

++++

Later that week, I was sitting in class learning about how American soldiers cleared the land of “hostile Indians” who kept attacking the “innocent American settlers” when my pregnant teacher suddenly stopped reading from the Florida History Teacher’s Guide and looked up at the door. Gail was standing there.

GAIL: Oh. Hi, sorry to bother you, Linda. I need to grab our rising artist, Danny Goldman, so we can hang his art show in the cafeteria.

LINDA [less of shits have never been given]: And?

I grabbed my manila folder from my backpack and we ran together to the cafeteria, laughing like bandits.

Inside, we hung — sequentially — the entire Adventures of The Cleaver across all the walls of the cafeteria. It was amazing to see it all like this: you could literally start by the entrance and read the entire story all the way to the end… and then get lunch.

That last part was Gail’s idea.

++++

The next day: school lunch was served by grade (Kindergarten through Sixth) in thirty-minute intervals, which meant Fourth Grade — my class — would go to lunch at 12:30pm. As we lined up outside the Cafeteria, I read the hand-written menu for the day: chicken-fried steak, mashed potatoes with gravy, peas and cornbread. The “steak” always tasted like a bad TV dinner but I was too nervous to be hungry.

My class, all two hundred-plus of us, filed into the cafeteria, most of the students looking up at my drawings for maybe a split second before lining up like cattle for their lunch trays. Food, choice of juice or milk, with individually-wrapped ice cream bars at the end, available only after you turned in your empty tray.

I took my usual seat at the weirdos table, watching the kids not-reacting to my work, when Jeremy Schenker leapt up onto the next table with a full plastic tray that he swung like a tennis racquet, showering the next table in brown gravy and mashed potatoes.

The whole cafeteria screamed at a pre-pubescent pitch as the war chant spread from table to table — FOOOOOD FIIIGHTTTT — and the air filled with splashing milk and flying peas and gravy and airborne slabs of chicken-fried steak. Even as a half-frozen orange juice cup erupted on the table in front of me, my eyes stayed locked on what was happening to my drawings:

Bright pink snail trails from strawberry ice cream bars slid down the front of The Cleaver’s very first adventure, smashed peas and sticky gravy coated The Cleaver’s descent into the Valley of the Devil-Dogs, chocolate milk bled together the Crayola markers I used to render The Cleaver’s transition into his replacement body. I watched it all unfolding in slow motion as every single one of The Cleaver’s adventures was ruined beyond repair in the three-minute food fight.

And through the slow-motion ballet of peas and flung ice creams and squirting juice boxes, my eyes met Gail’s blue-grey cat eyes framed by blue-grey cat-eye frames, so large, overflowing with a deep dark sadness that we now shared: the knowledge that we, the artists, were all alone in this shit-stupid world of ignorant pigs.

And though he had successfully transitioned into his stronger metallic body, The Cleaver was never drawn again.

Until today.

++++

Comments